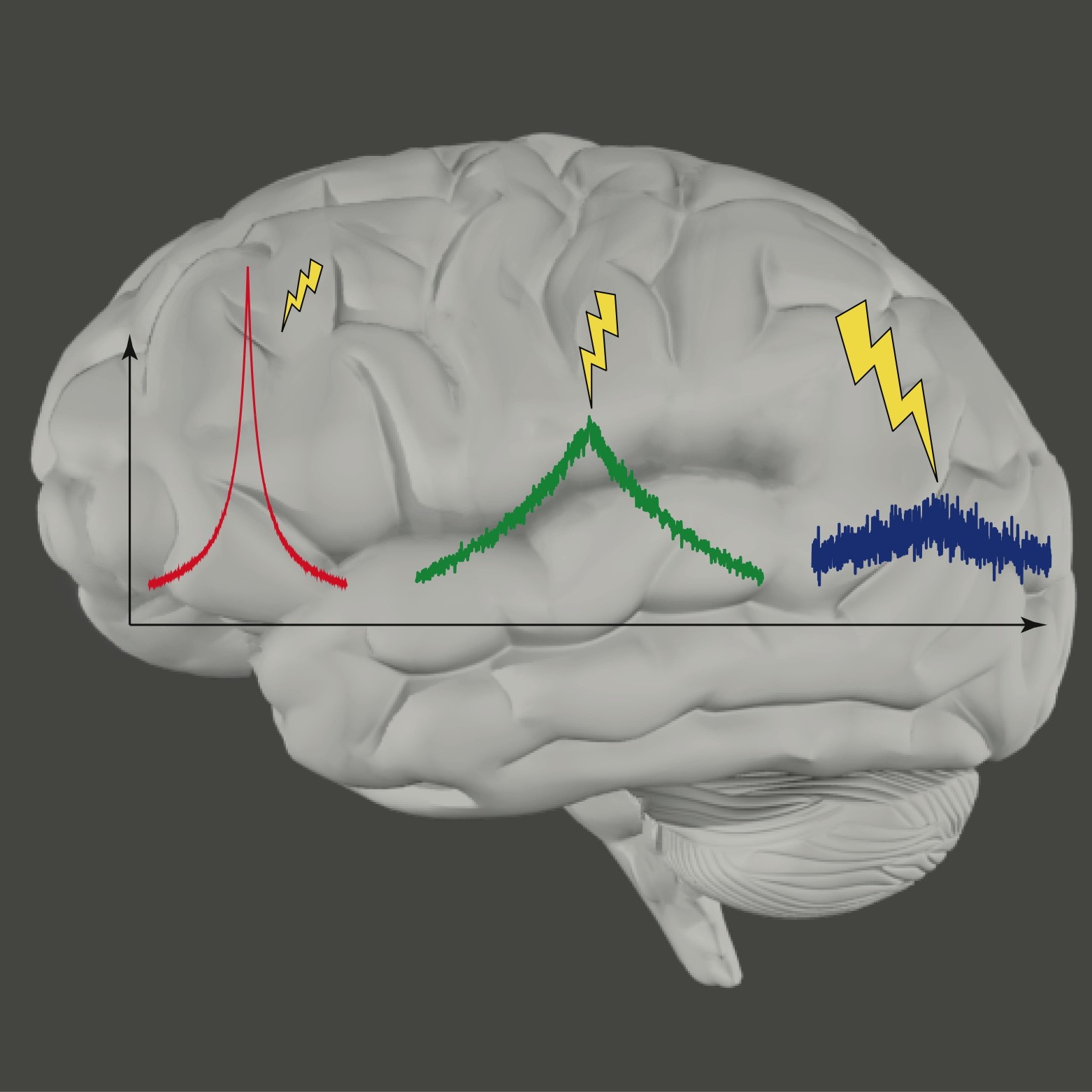

A constant bombardment of stimuli drives the brain’s dynamics away from a critical point to a “quasicritical” state.

Even while you sleep, each cubic millimeter of your brain’s cortex receives around 100,000 electrical signals per second. This constant bombardment prevents the brain from operating at its critical point, IU research suggests, in a manner that is simple and predictable.

The critical brain hypothesis argues that the brains of all animals—from turtles to rats, mice to monkeys—run near their maximum operating potential. Recent findings show a strong trend of nearly optimal information processing across many species.

But a problem has emerged. Activity levels differ between different brains, and sometimes within an individual brain over time, likely due to changes in external stimuli and behavior. Mathematically, the results suggest brain activity does not adhere to a single universality class, as would be expected. Yet somehow, the strong criticality trend still holds.

The IU team offers a solution to the paradox: quasicriticality. Their new organizing principle explains how neural networks can show signs of approaching the critical point, despite constantly changing stimuli and the apparent absence of a single universality class.

Quasicriticality fits data from recent studies as well as new experiments. The researchers grew mouse cortical tissue in culture, then measured its operations in response to different naturally-occurring levels of stimuli. The new proposal could substantially reshape brain research.

The research has been subject of a Viewpoint article in Physics.

Overloaded Brains Cannot Operate at a Critical State

Monday, March 1, 2021

The College of Arts

The College of Arts